‘How national is a national anthem? If you mean the melody, that’s a good question.’ With these words, scholar Alden Buker begins his short but thought-provoking article (1958) in which he highlights that many patriotic songs and anthems are sung to foreign melodies.

Buker’s article was written in a geopolitical landscape very different from today’s. But even in our age of globalisation and information (or disinformation), anthems continue to play a prominent role, being, according to sociologist Karen Cerulo, ‘the strongest, clearest statement of national identity’—and that’s despite so many national anthems’ not-so-national roots. Sounds rather confusing, doesn’t it? But history can play such tricks. Just as political borders and regimes change, so too do the meanings assigned to cultural artefacts.

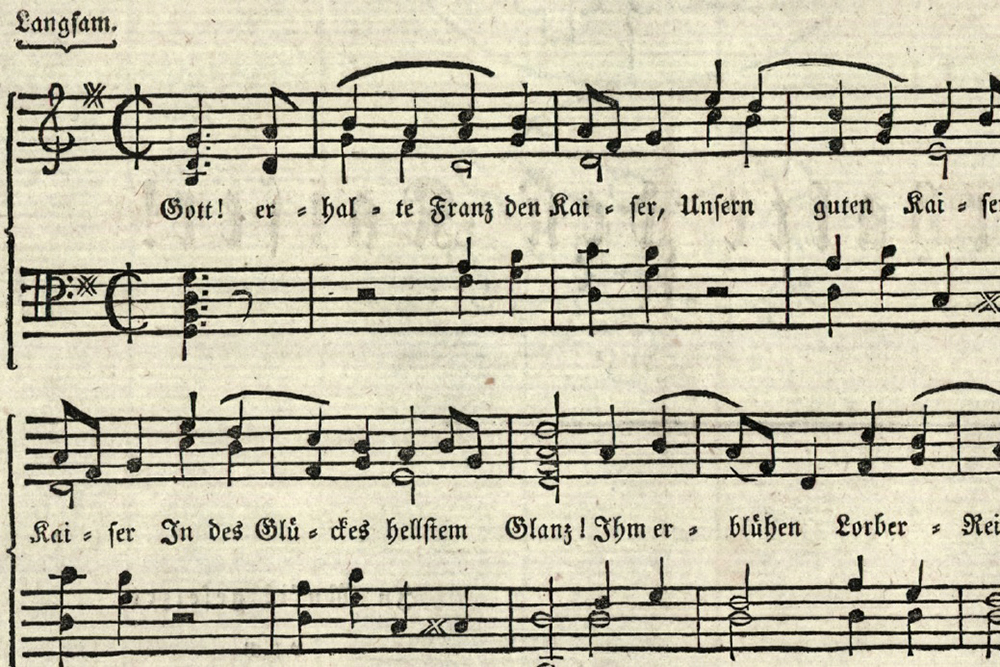

The story of Haydn’s ‘Gott erhalte Franz der Kaiser’ (‘God save Franz the Emperor’; words by Lorenz Leopold Haschka) demonstrates this like no other. It is widely accepted that the anthem, also known as the ‘Kaiserhymne’, ‘Volkshymne’ and ‘Kaiserlied’, was inspired by the British national anthem. Haydn believed that Austria—at that time threatened by Napoleon’s France—also needed a song which would lift the people’s spirit and encourage patriotism. Dedicated to Emperor Franz II, the work was first performed in Vienna on the Emperor’s birthday in 1797. Soon the anthem became very popular, and Haydn incorporated the melody into the second movement of his Opus 76, No. 3 (‘Kaiserquartett’, 1797). With varied versions of the text, the ‘Kaiserlied’ retained the role of Austria’s national anthem until 1918, and then again from 1930 to 1938 (until Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany).

Meanwhile, in 1841 German poet Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben wrote the ‘Deutschlandlied’, or ‘Das Lied der Deutschen’, which was sung to the melody of Haydn’s ‘Kaiserlied’. Fallersleben’s ‘Deutschlandlied’ became the official anthem of the Weimar Republic in 1922. Then, in 1933, Adolf Hitler, who described the ‘Deutschlandlied’ as ‘the holiest to us Germans’, adopted it as the Third Reich’s national anthem together with the Nazi party’s anthem ‘Horst-Wessel-Lied’. After the defeat of Nazi Germany, the ‘Deutschlandlied’ was banned by the Allied Control Council. But eventually, the third stanza became the official anthem of West Germany and, later, of unified Germany.

The ‘Kaiserlied’ and the ‘Deutschlandlied’ may have different names but they share the music which, undoubtedly, is now much more widely associated with the latter. And the ‘Deutschlandlied’, in turn, continues to remain if not the world’s most controversial anthem then certainly one of them. In the 2010 film The Debt, the ‘Deutschlandlied’ becomes both a form of punishment and a victory statement, when an Israeli agent walks to a piano and sings the anthem’s first verse to ‘torture’ his prisoner, a former surgeon from Birkenau. While there is no way of knowing what future Haydn envisioned for the tune, we can probably safely conclude that this is not what he had in mind…

Alan Marshall, the author of Republic or Death! Travels in Search of National Anthems, once proposed an explanation as to why famous composers rarely write national anthems. Marshall’s answer is simple: politics. Sooner rather than later, an anthem would be ‘sung by people you don’t like, or in a context you can’t bear’. Haydn did write one but, according to Marshall, in a way it became ‘the biggest failure of his career’.

The music historian in me is all against drawing such conclusions—deeming it a failure on purely political grounds sounds even more simplistic than blaming Wagner for Hitler’s ideology (see Joachim Köhler, Wagner’s Hitler: The Prophet and His Disciple, 2001). ‘Would he [Haydn] have composed had he known?’, wonders Marshall. We can never be sure. But perhaps, precisely the fact that the ‘Kaiserlied’ was anything but a failure from the musical point of view led to so many political establishments trying to use (and, at times, abuse) it.