‘Hell is full of musical amateurs’, wrote George Bernard Shaw in his 1903 play Man and Superman, and anyone who has heard an adult learner playing ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’ out of tune on a cello might be inclined to agree. Surely no one would opt to listen to an amateur musician over a professional? But one exceptional case does suggest otherwise.

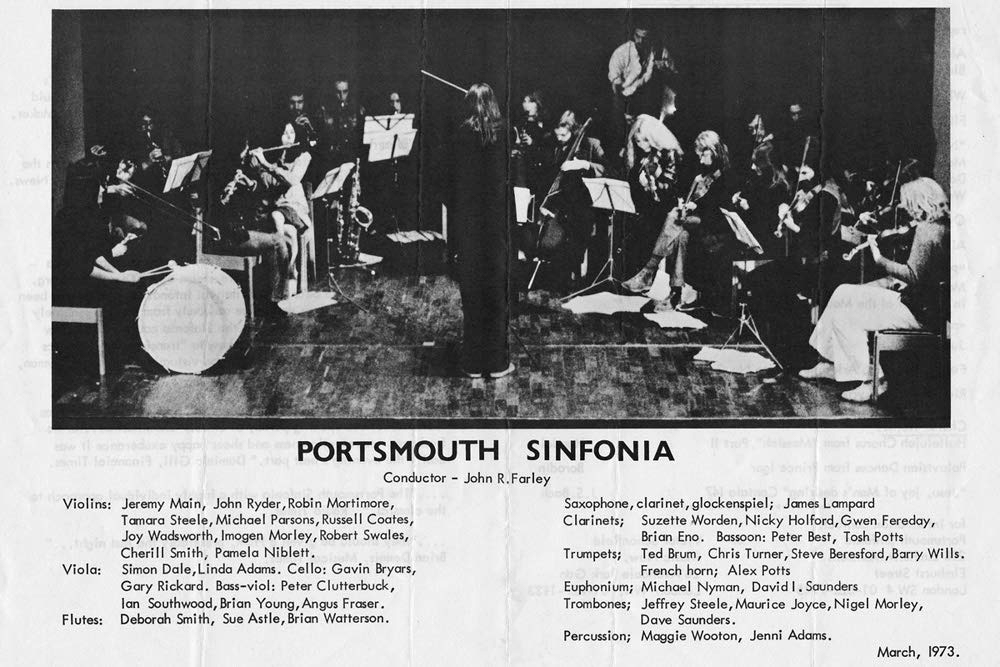

In 1970, a group of students from the Portsmouth School of Art decided to set up a symphony orchestra of people with no musical training. If a musician did ask to join, they were encouraged to play an instrument that was entirely new to them. The Portsmouth Sinfonia played popular classical pieces, from Rossini’s William Tell overture to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, though, on first listening, this isn’t entirely obvious.

Playing so spectacularly out of tune and out of tempo, the Sinfonia’s versions of popular classics barely came close to what is written in the score. But therein lay the appeal. The orchestra became a cultural phenomenon, playing in such esteemed venues as the Purcell Room at London’s South Bank Centre, and selling thousands of tickets at the Royal Albert Hall in 1974. The Sinfonia performed terribly for almost 10 years, until 1979.

What was the key to their unlikely success?

The most obvious (and cited) reason was their comedic value. Their recording of Also Sprach Zarathustra, for example, can lift even the lowest of spirits. That said, the comedic effect wears off quickly, and the Sinfonia’s founders always denied that the orchestra was ever intended to be funny. In fact, admission to the orchestra was based on, first, attending all rehearsals, and second, always trying to get the music right. So while comedy was a welcome by-product of amateur music-making, perhaps the ensemble’s success was down to something else.

Don’t the two guiding principles of the Sinfonia—1) attend all rehearsals and 2) always try and get the music right—sound strangely professional? Rather than expose a huge chasm between the professionals (perfect and god-like) and the amateurs (imperfect and recognisably ‘human’), maybe the Portsmouth Sinfonia shows that bad and good playing sit slightly closer to each other than on first listening. When asked if he thought that someone ought to learn an instrument in the privacy of their own home rather than inflict their inabilities on an audience, the professional double bass player, composer, and one of the Sinfonia’s principal founders Gavin Bryars answered: ‘most bass players tend to play wrong notes permanently, there’s a sort of history of playing badly in public anyway’. Bryars seems to think that the pros have been pulling the wool over our eyes in claiming to be anything but glorified amateurs.

It is perhaps in the Sinfonia’s choice of conductor, John Farley, that this uneasy proximity between amateurs and professionals is most obvious. Chosen purely based on the fact that he looked most ‘conductorly’, Farley is actually quite convincing. Because what is a conductor other than someone who waves a baton in the air and is seriously trying to get the group to play together? Similarly, what is a musician if not someone whose playing will inevitably fall far from perfection every time? We imagine that professionals are distinguished by their superior technique, but the worst orchestra in the world reminds us that the music industry often cares more about image and marketability than actual skill.

If the Portsmouth Sinfonia exposes the shaky foundations of professional music, it also shows that the seemingly doomed exercise of playing music together can be profoundly moving. This is most clear in the Sinfonia’s recording of the Hallelujah Chorus. Seeing people trying so hard to get it right while constantly getting it wrong, falling at every hurdle, ploughing through, determined to persevere while the reason for doing so in the first place is unclear, and doing all this smiling and united, is a beautiful thing. And it is this same absurdity that makes professional music so moving. Perhaps professionalism and amateurism are two sides of the same coin, and occasionally even indistinguishable. Accompanying a (genuinely professional) concert pianist playing Tchaikovsky’s piano concerto, transposed from B flat minor to A minor for convenience, one member of the Sinfonia, Robin Mortimer reminisces, ‘there was just a magical moment at the Royal Albert Hall during the piano concerto where even to a vaguely trained ear, it just sounded absolutely right… and then it became the Portsmouth Sinfonia again’.

It is a wonderful irony that the Sinfonia supposedly stopped playing only because they got too good at their instruments. Maybe it’s just in the midst of a pandemic today, where the unruliness of live music-making both professional and amateur seems very distant, but I think the worst orchestra in the world teaches us an important lesson: while so much can go wrong when people get together to make music, occasionally, good things come from muddling through.

If hell is full of musical amateurs, heaven probably also has its fair share.

Further reading

Seismograf article on amateur music making

John Kratus, a return to amateurism in music education

Rules on surviving amateur orchestra rehearsals